Background on Fed Bond Purchases

The Fed embarked on asset purchases, which they call quantitative easing or QE, during the global financial crisis 2007-2008. The move was motivated by a complete loss of confidence in the financial system. As a result, investors and financial institutions feared losses due to large-scale bankruptcies. Liquidity dried up completely and money was hoarded in allegedly safe places. The Fed stepped in with various measures and effectively returned confidence to markets. Quantitative Easing was among these whilst it was applied for the first time in US monetary history.

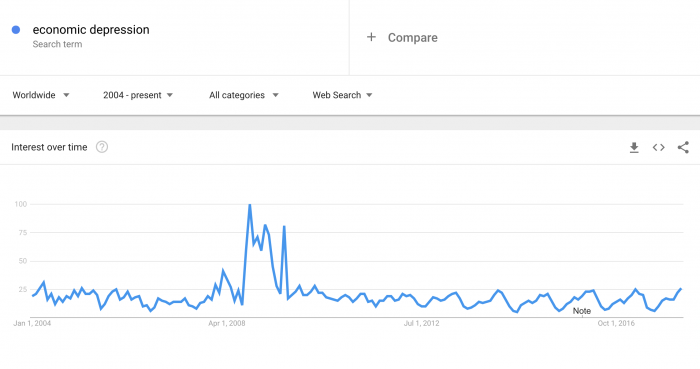

The determined intervention probably contributed to preventing a larger crisis. At that time people feared another great depression. It may have been forgotten today but the first chart below shows the Google search term “economic depression”. Countercyclical policy and confidence building are enormously important in such situations.

Market Intervention Dominates Interest Rates

The Quantitative Easing program was extended after the crisis in order to stimulate the economy. The Fed continued to buy assets like corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities. As a consequence, interest yields decreased to historically low levels.

Eventually, animal spirits returned back to the markets and the money that was parked in safe-haven assets searched for reinvestment opportunities. Obviously, low-interest rates across the board channeled capital into other assets. That is a side effect of the market intervention. Especially equity investments prospered during the past 10 years. Liquidity was attracted first by attractive valuation and dividend yields and later by market momentum. Corporate America found it also easy to borrow money. Luckily, the market could count on the Fed to find a reliable buyer. Hence, a large scale reallocation of liquidity took place due to monetary policy.

Inflationary Effects of Quantitative Easing

Quantitative easing isn’t automatically inflationary despite popular belief. It can be viewed as a Keynesian instrument for countercyclical policy (flattening economic business cycles). Asset purchases made during an economic contraction can be unwound during the subsequent economic expansion. Interest rates can be controlled through this mechanism. During expansions, liquidity can be taken out of the system again and interest rates get pushed to the upside.

The mechanism can be better understood with an example: Central bank bond purchases put liquidity in the hand of the seller. This liquidity is typically stored in bank accounts. It only becomes inflationary once the bank lends it to someone. The money needs to get back into the economy in order to multiply. Hence, liquidity from QE purchases that ends up in a bank account does not fulfill this requirement and is therefore not inflationary. The bank must be willing to lend the money and someone must be willing to borrow the money, which resulted from QE. This is often difficult in practice.

Most people tend to be rather pessimistic and cautious during economic downturns. They fear to lose their job for example. Borrowing in such situations to upgrade to a new car is subdued in such cases. This is regardless if the bank offers a 1% or 5% interest rate. You will not upgrade to a new car if you fear that your job is not safe short term! Banks are also often reluctant to lend during economic downturns. The decision process is directed by people who tend to be more pessimistic about potential outcomes during economic downturns relatively to expansionary periods. You may have already encountered the situation: “10 years ago it was easy to get funding for project XYZ but now banks are much tougher”. Animal spirits are at work there – a term used by John M. Keynes to describe risk inclination of human behavior.

Central banks can monitor how much is lent out and step into the market eventually. Assets can be sold from the balance sheet once the business cycle turns.

The theoretical outcome of QE results in a socialization of the debt burden. Central bank exposure implies that the outcome, positive or negative, will be passed on to the taxpayer. It also means that an economy can kick its debt burden longer down the road. The deleveraging process of an economy gets extended as QE resembles a new instrument that entered central bank balance sheets on a large scale just recently.

Quantitative Easing in Practice

The theory behind quantitative easing is great. It is a modern instrument to steer monetary policy. However, practice does not always run 100% according to plan in our complex world. We witnessed for the first time that central banks embarked upon such a policy. There is no track record with sufficiently measurable results yet. Japan has been the first economic experiment involving QE. It started in the early 2000’s. The BoJ intended to fight deflation by bringing more liquidity into the system. We have witnessed this experiment now for more that one and a half decades in Japan and still do not record significant inflation there. Seeing no inflation in Japan due to QE is actually what should rather worry central bankers applying this instrument. It implies that the measure is either ineffective or uncontrollable. Therefore, the same probably applies to economic expansions. The financial system will have an extended monetary base that is either ineffective or uncontrollable.

Higher Inflation Eventually Likely

Western economies have reached historically high levels of leverage. Further debt-driven growth seems less likely than a deleveraging process in the near future. Growth has been subdued in comparable situations historically. The best results (least painful) occurred in periods of moderate inflation. It should be therefore quite tempting for policymakers to target an inflation rate of 4-5% along economic growth. This figure effectively halves the total debt burden during a 10-year period.

The problem is that the complexity of the real world makes it harder to achieve this target. Moreover, there are natural conflicts of interest between politicians who get elected for 4-5 year terms and long-term economic goals. Keynesian policymaking has not been properly applied in recent history. The US economy went with a sizable Debt/GDP position into the global financial crisis 2007-2008. A long economic expansion preceded this financial crisis. Diligent Keynesian politics would have resulted in a very strong financial position of the Government going into that crisis. Obviously, no politician wants to take the foot off the gas pedal and rather individualize economic success to their own account.

Similarly, central banks around the world expanded their mandate. Today, they are more powerful than ever before. Not only central bank balance sheets increased but also borders of what is acceptable and what not get shifted. The BoJ and SNB have, for example, bought risky assets such as equities. At the same time, they still do not have precise forecasting instruments to assess the exact stage of an economic cycle. Nor do they have a reliable assessment regarding the correct quantity of their policy instrument. Last but not least, no reliable research has been published regarding risk inclination and aversion cycles as of today.

Hence, the US faces an economy with a high debt level and some moderate inflation is the best way out. Central banks have a terrible track record in identifying asset bubbles as well as cycle turns. This makes inflation likely as soon as animal spirits return to the economy. It will probably overshoot the preferred targets of policymakers.

Rising Inequality & Other Effects of Quantitative Easing

Low interest rates lead to a reallocation of capital. Dividend yields and rental yields become more attractive on a relative basis. It should be no surprise that QE has led to a bull market in equities and stopped the correction in the housing market. It does mostly affect the top 1% as their wealth predominately consists of equity and real estate. QE resulted in inflationary asset prices. It was concentrated in economic sectors that saw expansion or particular interest from the top 1%. Housing prices in economically prosperous areas such as New York, London, San Francisco, and Silicone Valley reached elevated levels and even created bubbles in some areas. The past years brought a positive correlation between exclusivity and inflation. New York properties listed for $ 100,- million are most likely the result of that.

At the same time, it is more than questionable whether QE produced measurable positive outcomes for the bottom 50% of the economy post-2013. This leads to rising inequality. IMF economists show facts in this blog why inequality threatens sustainable economic growth and development. Their conclusion is that extreme inequality in the US makes major economic problems even worse.